THE ALARM CLOCK AND THE CHARCOAL, OR ...

“Drawing 1973-1980 Maria van Elk”

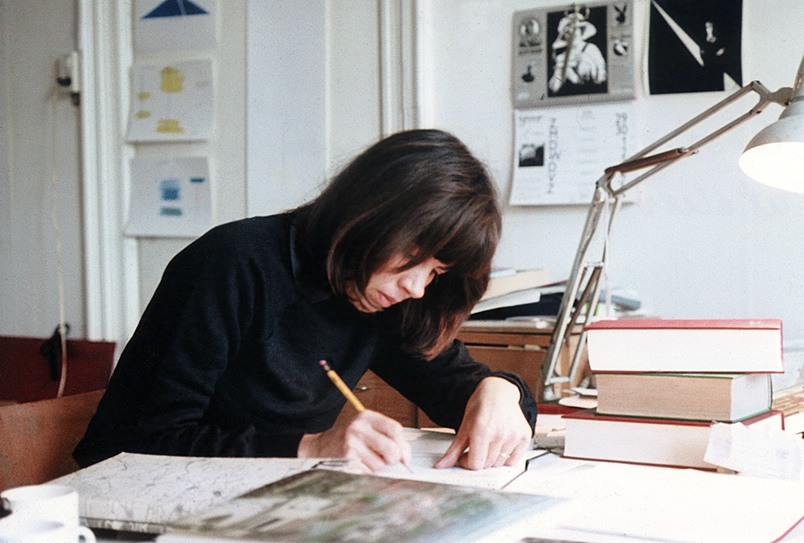

Being an artist prevails for Maria van Elk.

Therefore she consented to a picture of

her work instead of one of her face. For this artist

the personal background is of no consequence

Maria van Elk has, for the sake of clarity, indicated the start and end time on her “ 5 minute drawings”. With that she has made visible the element of time, which is seldom verifiable in an piece of art, namely the time it took to make it.

She set her alarm clock and started with charcoal to make rubbing movements on paper. Down, up and down again until 5 minutes passed. She repeated these movements with drawing chalk, with pencil and finally with indian ink. Four time-drawings of which the first covers almost the whole surface, while the last one covers only a minimal column.

“Onetime you draw fast, and another time you draw slow, you can of course steer this to a certain extent. But as an idea, as concept, I found it interesting that each material has its own time, because that is the essence of it”.

Until April the 6th the “Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam” shows a retrospective of the work of Maria van Elk, born in Amsterdam. This retrospective is called “Drawing” and not, as would be more obvious, “Drawings”. It is the act, dealing with pencil and paper, that matters in her work; the importance of the result is directly related to how the act is expressed. Thinking, and the material form of thinking coincide.

In two halls of the Stedelijk Museum monumental oil pastel paintings are shown alternately with subtle pencil drawings.

The thread that runs through this work can be reduced to two aspects:

a. working with the properties of the materials used

b. playing with geometrical forms

With these 2 points this is a subdued affair if you want to compare it with the exuberant paintings of the young Italians who exhibited in the same hall previously. The wealth of Van Elks' drawings is more subtle and this stands out only after you look attentively.

The works are accompanied by a text in which is described accurately what has been done with pencil, paper, cloth or oil pastel, and why. These texts originate from the book “Maria van Elk drawing 1973-1980” which serves as a catalogue. This catalogue was written by Coosje van Bruggen, an art historian, who managed in her usage of words to make a perfect parallel between text and art.

Nor in the drawings, nor in the text you will find ambiguities, references or metaphors. No lively stories, whereas in the work exhibited there is also no emotional handling of paint. Here a logical thinker comes into it's own, who will immediately be confronted with a direct attack on this logic, but more about this later.

The flat surface

First of all there is the flat surface. A surface that is totally different from a surface that carries a perspectival image of something. Of a landscape for instance, invoked to us as if one looks outside through a window , a phenomenon that is called illusionary.

Maria van Elk says about this “there are two ways to look. The acquired way is one of them: looking is immediately translated in depth. If something is depicted smaller it must be further away.

However you can also “translate” a diminution as something that is indeed smaller than something larger, but in the same plane. Illusionary watching hinders a certain way of observation”.

Not an image of reality, but the reality of the material. Material that determines form and composition.

“Looking back I think: I probably have a great sense of ownership. I find it difficult to annex things that are not mine. When you paint a landscape you annex something. You size things in a way.

Often I find this pretentious. I find a lot of art extremely pretentious and gross because of that. What I do is to show what is the property of the material.Let it keep its value, or actually amplify it. It originates, I think, from a strong sense of anatomy”.

Lithographs

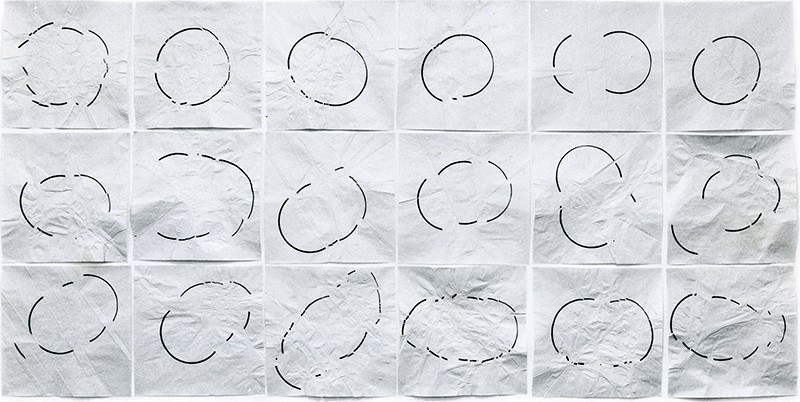

The series of lithographs (see above picture) are a good example of this. Maria van Elk printed circles on sheets of paper which she wrinkled and folded before. After printing the circles the creases were flattened and what remained visible was an disrupted or crumbled circle. The pressure of the litho press remains visible in the creases, while the different copies (18) in a formation of 3x6 clearly show that number 1 is clearly different from number 18.

Like the folding may be considered as a find to emphasise the fact that a lithograph is a picture printed on a press, likewise, the circle proved to be the optimal form to do justice to reproducibility, the fundamental property of graphical art.

The success of this, from the essence of an in graphics born idea, lies in the application of it. As surplus it produces both restiveness and monumentality, how contrary these two may seem. The visual delight that can be experienced follows according to Van Elk from the focus on the material.

“Nothing is added from anywhere else, it is fine because it is good, and it belongs only to itself and nothing is foreign in it. I think it is beautiful because it is itself”.

Integrity, it is the fresh air for her artistic breathing.

Close the doors

That Van Elk was disgruntled with the COBRA inspired instruction she got at the Academy Minerva in Groningen is precisely in her line. These abstract-expressionistic paintings are open to all sorts of interpretations, and this vagueness pushed her soon in the direction of a clear figuration. Not in the traditional way, with oil paint and canvas, but with materials with which she could attend better the problems of the closedness and delimitation of colour planes. However, it did not stop at this phase, time and again she felt the urge to push the problem further.

One can not (physically) enter an image of a landscape. Via an environment (a soft living room covered with artificial fur in which one actually could enter and in which one could imagine oneself in a landscape) it became clear to her that she was not yet on the right track. The environments were an enormous success, but the public neglected totally what Van Elk had tried to express with these environments. Apparently, in her search for reality she had not yet found the right tool.This disappointed her and she looked for another medium. With language (as medium) errors would be impossible. She would like to have at her disposal pure concepts, and she looked for these in philosophy. However, forced by circumstances she had to terminate her studies, and found herself once again face to face with the visual arts.

“I thought by myself: if I have to continue in art, then only on my own conditions. But although I intuitively felt that a different reality existed, I did not know in what form and what it looked like. Consequently, I abandoned everything that was familiar and well-known. That I longed for consciously. I wanted to get away from the figuration, the imitative. However, in reality I ended up in a black hole. At this point I simply closed my doors. In order to discover my own reality, my own viewpoint, it was necessary not to get near all sorts of images of which I thought: this may be it. No, I thought, that way it will be the same as before. I have to be completely on my own and figure it out on my own. To concentrate on the plane, on the meaning of paper and on what a line looks like”

It is 1973. An art historical period occurs to this artist as a personal happening. Her pencil walks over paper and follows the boundaries of the plane, explores the horizontal and vertical directions and also once leaves the plane altogether.

Next ,a drawn rectangle, or a curved line is put on a sheet of paper, as a rhyme against the borders. Or a line with a thickened part that functions as a large projection of that line which in turn behaves as a plane. This way an early series develops. A series in which Van Elk returns to the foundations, and with which she builds for herself an insight in the plane and the line. But also a series which contains the germ that will be more explicit in later years.

Studio revolution

At that moment she has freed herself from all images that could refer to reality.

“Now I can discuss more easily the renouncing of citations to anything beyond reality more easily than before. Because, if you have not experienced it, it has no form and no meaning. In that case it becomes difficult to decide what can and what cannot be done. I wanted something of which I could think afterwards: Yes this is timeless. The moment you remove your own moods, you are left with something more stable and less subject to temporary preferences”

Slowly, step by step, this studio-revolution took place. In 1974 oil paste was introduced, and the pencil lines are dominated literally by this oil paste. In Van Elk's own personal handwriting, the back and forth scratching movement, on which also the time-drawings are based, she applies a thick trace of oil paste on the paper. This series is called “Line on and under”. The pencil line is abruptly cut by the oil paste and sometimes does emerge again further on. Interesting is the discovery the same year, that a card, put under the surface of a paper sheet, reappears after scratching the surface of the sheet without actually having drawn the form of the underlying card. A child may discover the same technique but usually a coin is used. However, for a philosopher interested in limits this may have a lot of consequences. Because it is such a curious paradoxical movement: again and again the movement is off the plane and on the plane again negating and underlining its limits. The pencil seems to make a sort of caper.

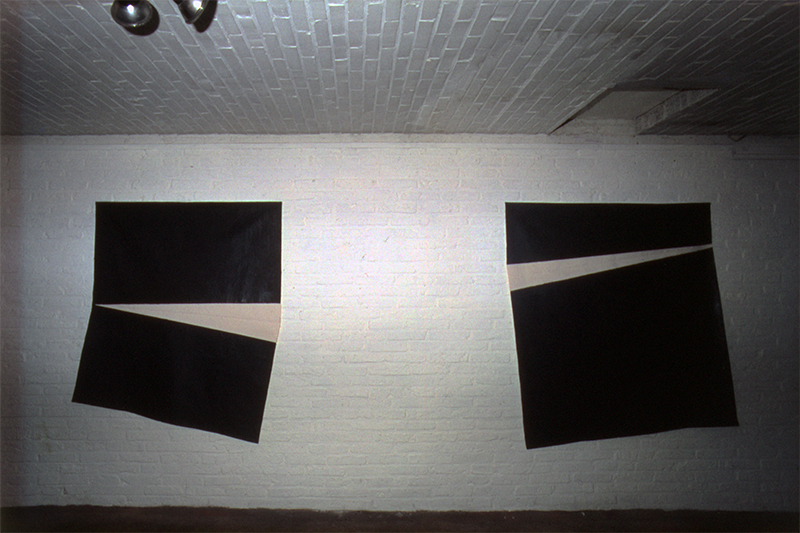

Later, Van Elk used this idea (the pencil making a caper) at a larger scale, on a canvas of 140 x 140 cm with a deep horizontal fold. Because the woof on the right was smaller than the on the left, the square shape was lost. She recovered the square again, including the fold, and drew the new square with black oil paste (this oil paste is a not shiny compliant chalk that looks like oil paint, but does not coalesce, so that the pressure of the hand seems moulded in it).

When the fold is unfolded it permeates the black area as an untreated blind area, and splits the square with its added surface. The lower part revolves to the right and hangs clear from the lead.

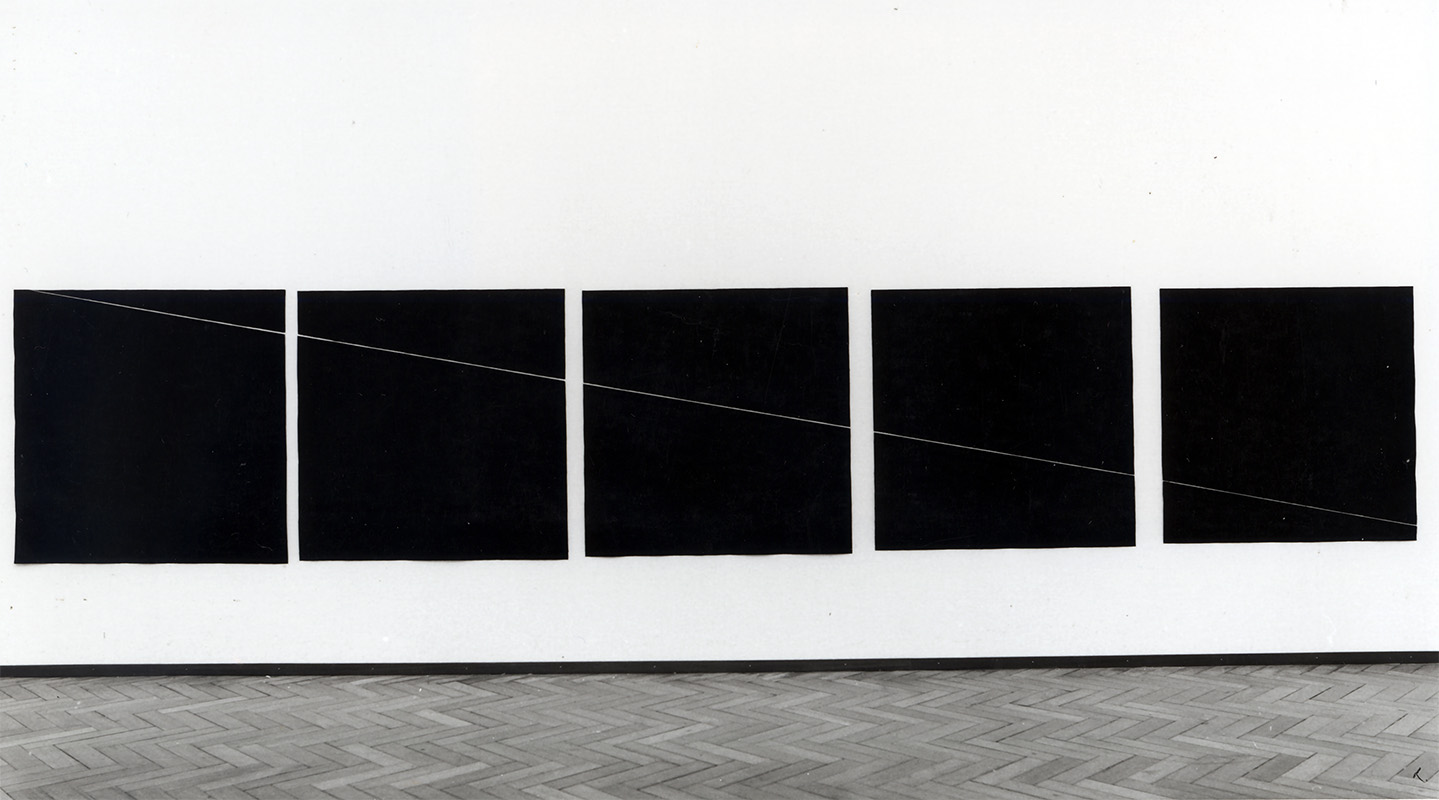

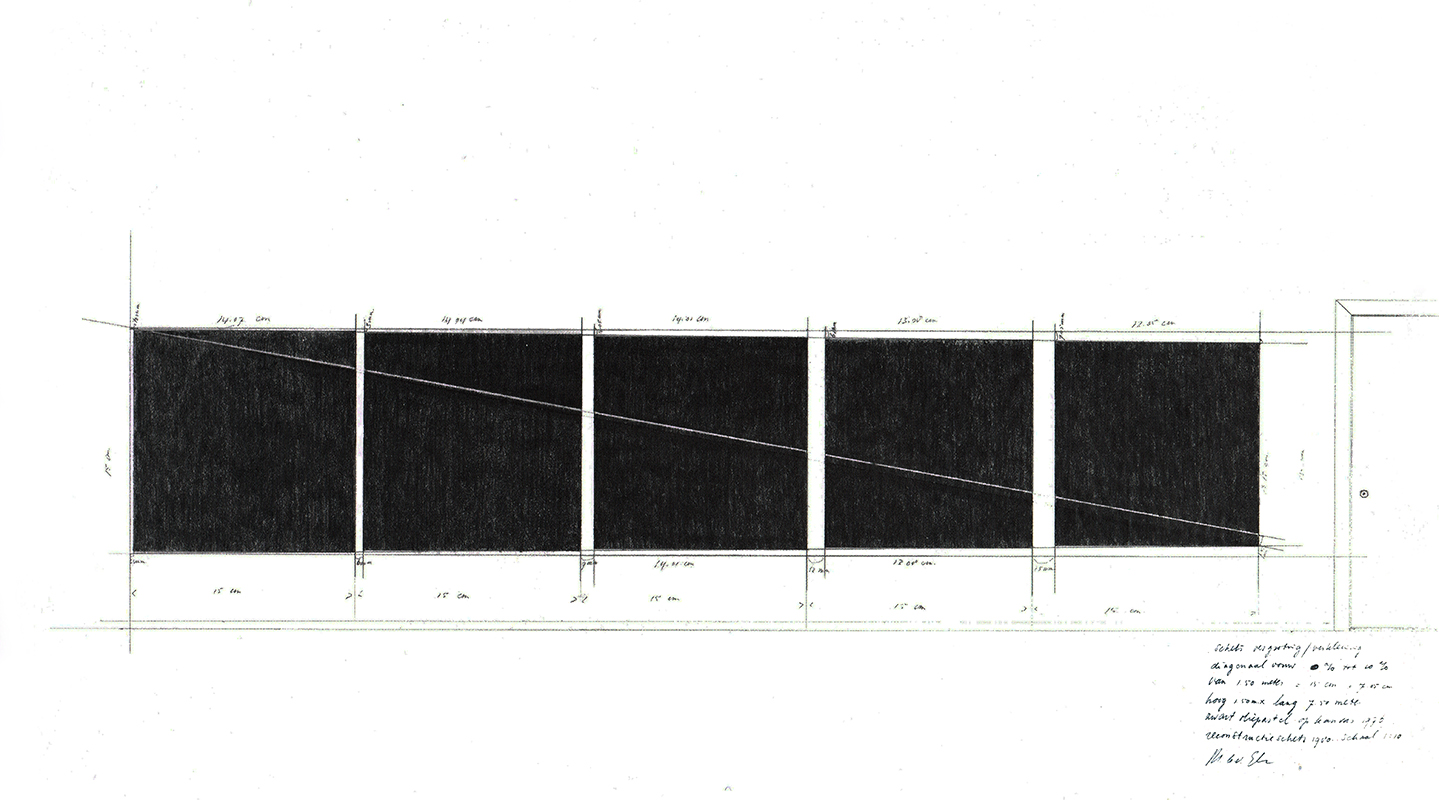

In 1977, a more substantial enlargement resulted in a monumental five-parts work that is the high-light of this exhibition. In this work however, the fold remains closed. The fold, going from zero in the upper-left corner diagonally across the 5-parts to the lower-right part, looks like a white, but also a black line on the canvas covered with oil paste. The white line however is not drawn, but appears at that part of the canvas that is not touched by oil paste because of the fold. The reverse side of the fold picks up extra oil paste with frottage, creating the black line.

These two complementing “zero lines” take their shape directly from the material and are not drawn.

Because the depth of the fold increases gradually from the part on the left-side to the part on the right-side, the remaining square decreases in size gradually. With this a simultaneous movement of enlargement and diminution is set into motion: a measure rhythm with diagonals that, although they have come about as accidental leftover lines, function in this case as stable constants. An inverse logic.

Her work abounds with these paradoxes.

These paradoxes are also visible in the two-layer square in which the unfolded, crude canvas sheet, that remains in the sheet covered with black oil paste, is the first-phase remnant in the second phase square.

It seems an abstract story. It is not essential however, to have an intellectual background, for at a first glance one becomes fascinated by the witty contradictions.

A canvas triangle with a 5 meter base is the most recent work. One half is covered with yellow (oil paste), the other half with blue oil paste. “triangle folded to triangle” of which a yellow triangle is folded in. The unfolded example is also present, “triangle unfolded to triangle”.

Van Elk notes:”All folded forms change in form”. However, when I folded this triangle it appeared, to my surprise, that after unfolding I was left with exactly the same triangle, but now swung over. This was a very exciting discovery. That is something I could not possibly have conceived. These things come with working with the material.

Formerly, I assumed that if I concentrated on things I was working with, it would also contain an unbelievable richness with which I could continue working. If I only had the time for it. Exhibitions and people around me distract me enormously. I function best if left alone on my atelier. That is the ultimate adventure for me. Only then I have the feeling things are improving. I can get get excited by it. Only then it is interesting to be involved in art”.

In my opinion there can be no question about this last observation of Van Elk.

Source: De Noord-Amsterdammer, March 27, 1981

|

- ferry andre de la porte.jpg)